My Daughter Finally Named Her Adoptee Pain

I could see in my daughter’s eyes that she was on the verge of tears when she called to FaceTime me on a Sunday morning. I asked, “What’s wrong?”

She said she was sad and didn’t know why. She thought it was just hormones, but I sensed the underlying cause. I had created her pain by relinquishing her for a closed adoption when she was an infant, almost 50 years ago. I’ve been studying research on loss relating to adoption trauma, and I’ve also read that a woman’s cycle activates past hurts and traumas that have not healed.

I, too, had been adopted as a baby. Even so, I still gave my daughter up when I was 15—many years before I searched for and found my own biological family. My daughter and I were reunited on her eighteenth birthday, when her parents flew her from the Midwest to California so she could meet me. On the outside, ours looks like a normal long-distance mother-daughter relationship. We talk regularly, trade recipes, and share diet and beauty tips.

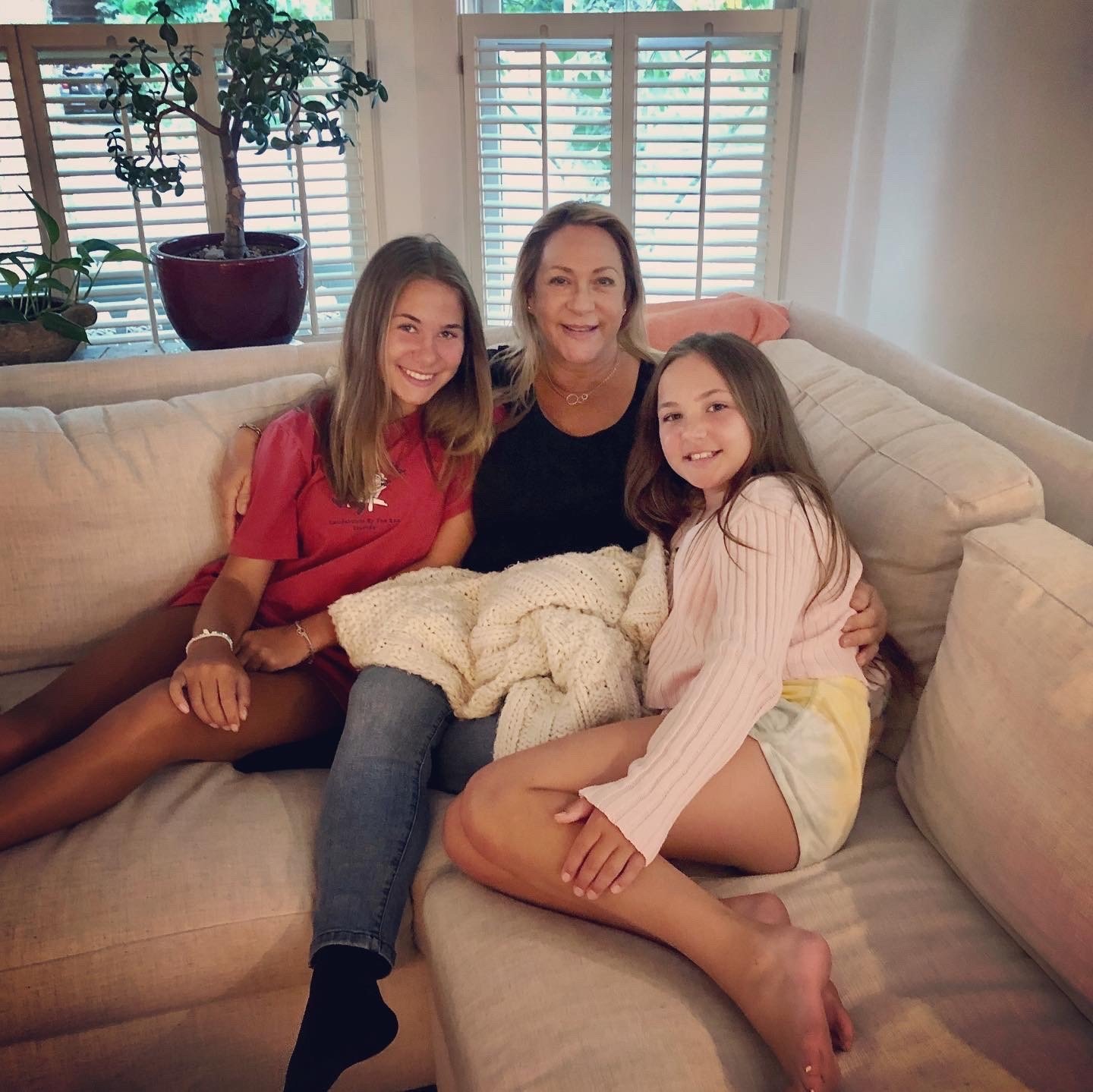

We’re a lot alike, too. We share the same hobbies, love to decorate, and have many of the same clothes in our closets. We finish each other’s sentences and even bleach our brown hair. It’s as if we were in utero together. People often can’t tell us apart, including her mother. When viewing social media photos, I sometimes do a double-take, not sure which of us is on the screen. Yet we have only seen each other in person a dozen times in 50 years.

While talking with her that Sunday morning, I tried to take her mind off her sadness by asking about a recent trip to the zoo with my granddaughters. She seemed to be feeling better when she inquired about my favorite features on the smart home device we both owned. She also wanted to know the best way to dispose of the containers of spoiled chili that were stacked on the kitchen counter. “Garbage disposal or trash?” she asked. I recommended not putting so much down the drain for fear of clogging, but she felt bad contributing to our landfills.

In the middle of our exchange, she turned away from the phone and began to weep. I felt as if my presence reminded her why she was sad. I think the warmth of our conversation reminded her of the miles between us. She can’t drop by when she needs me. We can’t have coffee, go for a mani-pedi, or grab lunch.

Guilt washed through me. Her need for me to comfort her fulfilled a longing I’ve had since I left her at the hospital. As I indulged my maternal instincts, she suffered.

“I’m making you sadder,” I said. She sobbed.

When she called, I had instantly recognized the look in her eyes. I’d seen it a number of times over the years. It was like she was hanging in a dark well, clinging to a rope, her eyes beseeching me to pull her up. One would think my daughter wouldn’t miss me since she didn’t know me when she was growing up. But she did. She once told me that she always sat by the window on her birthday, crying and waiting for me to come for her.

In her book The Primal Wound, psychotherapist Nancy Verrier explains the damage done to adopted children who are rejected by their mothers. She describes the wound as “physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual, a wound which causes pain so profound as to be described as cellular.” Because I gave her up, my daughter felt empty during her childhood—a feeling that followed her to adulthood.

I wanted to teleport to the Midwest and comfort my daughter, tell her I was sorry for giving her up, explain that I understood her sadness. That all my life, I had also yearned for connection—but to what, I didn’t know. Although I had a deep love for my adopted family, something was always missing, like a shirt held together with just one button. It doesn’t quite fit and will never be whole.

I feared that naming the source of her pain would cause more anguish. She hadn’t identified it yet, and it wasn’t my place to identify it for her. I worried she would figure it out with time, just as I had. I’ve heard other adoptees refer to it as “coming out of the fog,” realizing their grief comes from the loss associated with being disposed of at birth by their own mother. This is the ultimate betrayal—betrayal adoptees are expected to be grateful for. I worried that taking the blame for her suffering would make her resent me.

I forced back my own tears and listened to her weep. With her head still turned, her cheek and right ear filled the screen. Just then, my concerned nine-year-old granddaughter rushed to her and said, “Mommy, why are you crying?”

She shifted to embrace my granddaughter. “I just miss Grandma.”

That was the first time she had ever named her pain. I wanted to cry too, not for my loss but for hers. She has called me on and off over the years with an unidentified sadness, but until that moment, she had never once identified what I have always suspected is the root of her pain: she misses me.

My only comfort during the 18 years before our reunion was my belief that she had an abundance of love in her life. The Sister at the adoption agency had told me how excited and anxious her new parents were for me to give birth. My daughter was 30 days overdue and her adoptive parents wanted me to drive over a bumpy road to induce labor. The very day I left her at the hospital, they scooped my baby up and took her to her new home.

I have imagined the scene over and over: a respectable couple seated in the lobby, waiting in reverence as nurses bustle by in silent white shoes, aprons, and starched caps. I picture the mother holding a freshly packed diaper bag, waiting for the signal that the coast is clear; the birth mother’s car has left the parking lot. I see my baby in her new mother’s arms, then her father’s, the two of them replacing me in the very room where I had said goodbye moments before. But not long ago I learned they picked my daughter up at the Catholic Charities office.

I have now been part of my daughter’s life longer than I was absent from it. We had both counted the years until she turned 18 and we could find each other. Our reunion was the beginning of healing our wounds, but a mother’s absence from her child can never be made whole.

Maybe I feel her pain so acutely because I am adopted, too. I know the underlying grief that she feels. When my first mother gave me away, she left a hole in my heart that will never be filled. Unlike my daughter, I never got to meet my birth mother—as an adult, I learned that she had passed away when I was seven.

While my daughter cried on the phone that day, I had a close-up view of her right ear, which caused me to flash back to being 15 and holding her in a hospital room adjacent to the nursery. Because I was adopted and had no known blood relatives, no one on the planet that I resembled, I carefully examined her little body for similarities. I was delighted to discover that she had my long second toe. Many years later, I heard the old wives’ tale that a woman with that long toe will rule her family—and we are both a bit bossy. I also noticed that, unlike me, my daughter’s ears were asymmetrical. Staring at her ear on my screen was the strangest feeling, as if I had one foot in the present and the other in that hospital so long ago, studying cheeks and temples so similar to my own.

The nun who facilitated the adoption sent me two Polaroids of my baby girl, both taken at her new home. She was propped up and looking into the lens, covered by a white knit blanket. Her two little hands stuck out like puppy paws. I wore the edges of those photos raw taking them in and out of the envelope so many times. I still have one but lost the other, the one showing the side of her face with the oddly-shaped ear.

I’ve read that fetuses hear sounds from outside the womb, then retain those sound memories after birth. New research suggests that fetuses can memorize their mother’s voice and the songs she sings as early as 16 weeks. While I was pregnant, my mother and I prayed the rosary, with its 50 Hail Marys, nearly every night for six months. We repeated it literally thousands of times on our knees in our living room, praying my baby would be healthy and have good parents.

So, it’s no wonder my daughter’s go-to prayer is the Hail Mary. One winter, when she was distressed by marital problems, I visited her at Christmas. We went to a Catholic church on a dark, snowy evening because she wanted us to pray the rosary together. It was cold as we knelt inside the empty church and repeated the string of Hail Marys out loud together. I felt oddly comforted kneeling in the pew next to my daughter, which surprised me because neither of us is religious. And yet she still has the Virgin Mary statue I asked the Sister to give her parents nearly 50 years ago. It sits next to her bed on her nightstand, as it always has. When she is worried, frightened, or scared, she looks at it and repeats the prayer to the mother of all mothers, the Virgin Mary. When I echoed those words while I was pregnant, I had no idea she could hear my voice. I didn’t know I was giving her something she would draw comfort from through her entire life.

When I was two or three years old, Mama often repeated my origin story. Before bedtime, she would tell me I was special. She said my other mother loved me so much that she gave me up so I could have a Mama and a Daddy. Now, I realize that my favorite bedtime story had groomed me to relinquish my baby. Even though giving away my infant—the only flesh and blood I knew, the life I carried and sustained in my womb for almost a year—went against every grain of nature and assaulted my innate maternal instinct, I heard in that bedtime story that it would be selfish to keep her.

Regardless of the circumstances, I am at fault for her pain because I was her mother and I gave her away. Yes, my parents, the nun I counseled with at Catholic Social Services, and even our societal norms groomed me to do the “right” thing. Throughout the pregnancy, I was never presented with the option to keep her—that is, until two days after the birth, while I was still in the hospital, just before the adoption papers were placed in front of me. The nun conveyed a message that my mother had been too emotional to deliver: she couldn’t live with herself if she separated a mother from her child. I could bring my baby home if that’s what I found in my heart to do. But I signed those papers anyway, and I can never take it back.

That’s why my daughter was crying when we FaceTimed. We talked for over an hour that day. I loved how her face filled my screen with an image that reflected my own. Even though she was sad, and even though we weren’t sitting across the table from each other for a Sunday morning coffee, it felt good to be with her. When we said our goodbyes, I reluctantly pressed the button to end the call. I was stabbed by the immediacy with which her face vanished from the screen. Losing her again always brought me pain. I’m sure it hurt her, too.